A punishing weather day gave a bunch of new nicknames to the 32nd annual Gulf Coast Triathlon in Panama City Beach on Saturday, May 10, 2014:

“Gulf Roast Triathlon”

“Gulf Coast Windathlon”

“Gulf Coast Humidathlon”

“Gulf Coast Suckathlon”

“69.1”

Nonetheless, 35 members of Gulf Winds Triathletes fought through difficult weather conditions and finished the event.

Race officials cancelled the 1.2-mile swim 10 – 15 minutes after the race was supposed to start. Before the cancellation announcement, the 696 participants milled about on the beach at the water’s edge, preparing for the swim start like any other race. There seemed to be more activity than usual in the water, though, with Sheriff’s boats, jet skis, and several kayaks moving around, rather than holding positions. As the start time came and went, more people turned their eyes and conversations to what was happening in the water. A 15-mile-per-hour due east wind had stirred up the Gulf, and the waves blew in from the southeast, different from the predominant southwesterly wave patterns at Panama City Beach. The onshore waves were strong and three to four feet high, challenging to get through but nothing terribly unusual for that beach at that time of year.

Then a jet ski flipped over in the waves. Kayakers were seemingly constantly paddling but were grouped together and had difficulty separating from one another and moving against the southeasterly current. Some kayaks got flipped over in their efforts. A small Sheriff’s Department vessel circled the interior of course slowly.

Meanwhile, a lifeguard with a red flotation device tried a practice rescue at the breaker level, maybe 20 – 30 yards offshore. He charged full speed into the water, dove into the first wave, and looked like he got pulled back by the force of the wave grabbing his floatation device. He stood up, still in only waist-deep water, and charged again at the next wave. Same result: two steps forward, one step back. If there were a swimmer in distress 30 yards offshore, the lifeguard would have taken a long time to reach him or her. Eventually, the lifeguard stopped diving into waves, turned around, and rode a couple of waves in closer to the beach.

According to the report in the Panama City News Herald the next day, here’s what happened shortly thereafter:

For the first time in the event’s 32-year history, race organizers had to scrap the 1.2-mile swim due to rip currents and whitecaps on the Gulf of Mexico. Red flags were flying on the beach throughout the day, and race director Shelley Bramblett said safety officials were unable to put their kayaks on the water to provide a first-line safety measure.

“When you get a call that they cannot safely rescue people, it makes the decision easy,” Bramblett said.

The race . . . began instead with a [short] beach run and a staggered start by age group [where participants started individually, about 5 seconds apart in an effort to keep transition from becoming overcrowded]. The event’s 56-mile bike ride and the 13.1-mile run were unaffected.

Last year’s women’s champion, Kirsten Sass, crossed the finish line several minutes ahead of the rest of the [women’s] field . . . . She said she swam in the Gulf on Friday and saw that conditions had the potential to be dangerous for the less-experienced triathletes.

“I’m very understanding,” she said. “That is a hard call for any race director to make.”

While every 70.3 race has starters who do not finish, the preliminary race results showed nine people who did not even start after the swim was cancelled. Race conditions also knocked out 27 athletes who endured the strong winds on the bike course but who either did not start or did not finish the run.

Weather forecasts predicted that the winds would shift from the east to the south and remain between 10 – 20 mph as the bike race unfolded, and the forecasts did not disappoint. The first leg of the ride was a seven-mile flight west on Front Beach Road with a strong tailwind. As the route turned north on US 79, the wind seemed to turn, too, providing a healthy tailwind for the 20 miles of straight road. The bike course had two westerly spurs, each about 9 total miles down and back, and the first spur offered adecent, but not quite as strong easterly tailwind. The expected headwinds hit almost immediately upon negotiating the turn-around. The collective pace slowed noticeably during the 4.5-mile ride into the moderate easterly headwind.

The route then turned south on US 79, and the moderate easterly headwind turned into a strong, steady headwind out of the south. People who were riding 25 mph with the tailwind were now struggling to maintain 18 mph with the same effort. And so it went, with an occasional traditional wind swirl, where the headwind briefly dissipated, then blew from the side and pushed the bike a little, then returned to blowing directly into the face.

For many cyclists, the pace slowed even more for the final 6 or 7 miles on Front Beach Road toward transition. The easterly tailwind that was so enjoyable on the way out now became an easterly headwind that pushed some slower or exhausted riders into speeds in the low teens.

But for many, the best–such as it was–was yet to come. Those Tri Club members who competed in Tri the Rez in 54-degree water just 60 days before Gulf Coast were about to enjoy getting beaten by both ends of the same weather stick: vertigo-inducing cold in March, strength-sapping humidity in May.

“Humidity” can be described scientifically as a measure of water vapor in the air. No biggie. Water vapor is supposed to be in the air. It’s part of the circle of life, young Simba.

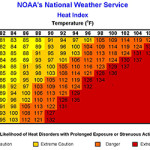

When the air is holding half as much water vapor as it can before forming dew, the “relative humidity” is described as “50%,” also known as “Arizona.” As more water vapor forms in the air, say up to 70%, scientists describe it as “kind of sucky.” When the humidity reaches 80%, it’s called “Tallahassee,” but only from inside air-conditioned laboratories; no scientists have actually gone outside during such conditions. To remind themselves not to go outside in high humidity, the clever folks at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration post a “heat index” chart by their front door, reminding them that heat is one thing, humidity is another, and combined, well, it’s just a really good time to re-read a report on Pacific ocean tides from 1843, as long as it can be done from inside.

By the time the half-marathon run started at the Gulf Coast Triathlon, the temperature had climbed to a seasonably reasonable 84 degrees, but the relative humidity stood at 94%. Six more points and we could have used fins and goggles on the run. Looking at the air-conditioned chart from our friends at NOAA, those conditions applied to the suck index, uh, heat index, meant the run felt like running in 100-degree weather. For 13.1 miles. In early May. On hot asphalt. With limited shade.

A joyful little biological dance begins when competing in such conditions. The body realizes it is overheating, so it pulls blood from extremities and pushes it toward the skin to create a cooling effect. Smart body. Sweat is produced to cool the skin and reduce the overall body temperature, which works great in Arizona where the evaporating sweat cools the body. But humidity is a classic bait-and-switch move. Just as the cooling sweat leaves the body at the invitation of the air, Humidity says, “Sorry, we’ve already filled the air with water vapor, so your sweat cannot evaporate.” Instead of producing a cooling effect, the sweating ends up increasing the body temperature, which means the heart sends even more oxygen-rich blood to the surface to try to cool everything again, unsuccessfully. And the cycle repeats.

None of which would matter too much, except that the human body is a closed vessel with a limited blood supply. All of that oxygen-rich blood vainly attempting to cool the overheated body surface—all the while disproportionately pumping blood furiously to the vital organs to keep them from overheating—must come from somewhere. And it does: it comes from the less relevant extremities, like the legs and the muscles inside them. And just like that, Tri Club member and triathlete extraordinaire Marci Gray, F40-44, who can peel off seven-minute miles for a half-marathon in her sleep, finishes the run at Gulf Coast with eight-minute miles, describing the race—even without the swim—as, “The hardest race I’ve ever done.” Eight-minute milers struggle to hold a nine-minute pace in high heat and humidity; nine-minute milers find themselves questioning their training when they see paces on their watches of 10-minutes-plus. Ten-minute milers decide it’s a great day for a stroll and end up bonding with aid station volunteers.

Through it all, though, there were some remarkable performances, as there are in every triathlon, no matter the distance or the conditions. Club member Don Autore, M35-39, finished 12th overall on the strength of an average speed of 24.6 m.p.h. on the bike, and a run pace of 7:24 per mile. No less remarkable were those who simply finished, regardless of time.

A cancelled swim, a windy bike, and a humid run: In the should-be-trademarked phrase of Club member Jen Barton: “Gulf Coast 2014: Worst 69 Ever!”

Click here to see a list of all Club members who finished, in descending order of time, regardless of gender.